The big art event over the 2020/21 summer in Sydney is the Arthur Streeton survey at the Art Gallery of NSW – the first since 1996 of this immensely popular artist.

This one is more comprehensive than the previous survey. All the better, because critical mass gives viewers the opportunity to really get a handle on an artist (in this case) who is often taken for granted and dismissed by many as hopelessly conservative. The received opinion is that Streeton did his best work before he left Australia for the first time at the age of 30 in 1897.

I think this view is wide of the mark and you can see why if you read my review of the show in Artist Profile (#54, February 2021). Right now, I’d like to float a few radical ideas about Streeton which space in the magazine does not allow.

First, Streeton was an abstractionist manqué and a painter who believed that the act of painting was more important than what the painting depicted.

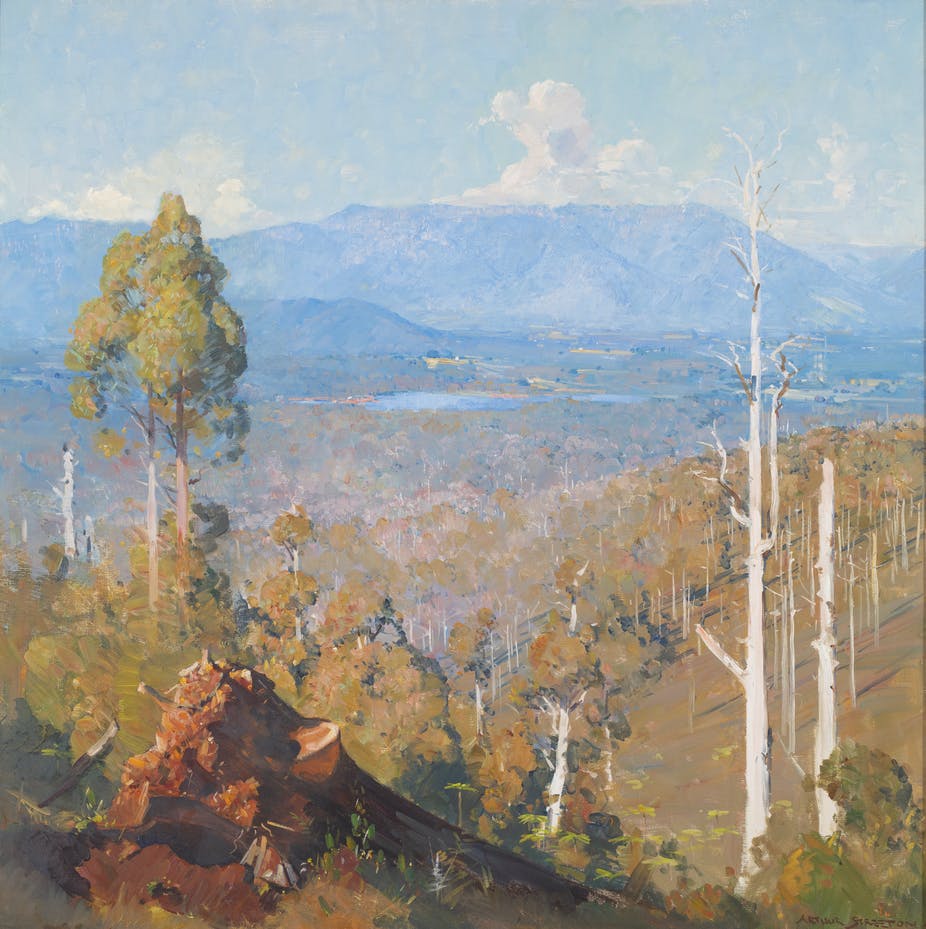

Even with the rural landscapes and the views of Sydney Harbour and Sydney beaches painted before he went abroad for the first time and which remain his most popular work the composition (or design) and sense of scale dominate the subject matter.

Take a picture like Early Summer – Gorse in Bloom (1888). Here we have Streeton’s typical – and emphatic – horizontal format clearly organised into foreground, middle ground and deep space. The foreground is the gestural, impasto gorse. The middle ground features an abstract arrangement of three vertical fence posts connected by a horizontal timber beam with a fourth vertical organising element – the young girl animated by the two red gestures of her hat and stockings. The deep space depicts practically nothing – just the horizon line and the blue sky with some cloud.

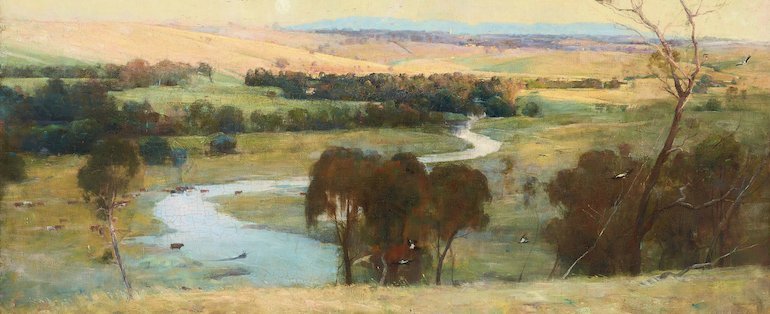

The tripartite division is a recurring theme, typically united by a meandering stream or path. Spring (1890) depicts practically nothing – a field, a clump of trees, distant hills and a river with some bathers. It is really a cluster of roughly painted tonal areas linked by a path and animated by Streeton’s favoured dash of orange-red.

It is a strategy seen over and over again in Streeton’s landscapes. Look again at Still glides the stream (1890) with its receding horizontal planes counterpointed against the verticals of trees all knitted together by the sinuous river.

That dash of orange-red, though, is most supremely abstract in Streeton’s tiny (24.2 x 13.3 cm) gem from 1897, House Builders, Cairo. With its flattened picture plane charged by a tension between surface and depth, this painting could almost be a manifesto both of Modernism and of abstraction. This is amplified by the tension between the almost geometrically abstract composition and the painterly surface. Once again the design is ignited by the extraordinary orange-red moment near the top of the painting which Streeton doesn’t even attempt to explain.

At the same time – that is, late in his career – Streeton re-visits the proto-abstraction of Constable’s cloud studies in pictures like The Cloud (1936), and note the white impasto vertical lightning in the upper right which again triggers the all-important surface tensions.

Finally – the online space, like the fell sergeant death, is strict in its arrest – a word about Streeton, paint and the surface. Like a painterly linguist, Streeton organises multiple meaningless elements into patterns to generate visual meaning. Get up close and these are just marks, visual gestures. Stand back and it all makes sense. Nowhere is this better illustrated in Streeton’s work than in his flower paintings – Lilies and Belles (1935), for example.

This is a Streeton who is now painting for himself and for painting’s sake. The subject of the painting is now just the excuse for painting as a creative act – an act which became increasingly direct and gestural. But his entire œuvre resonates with the abstraction of music with the brush marks and tonal areas generating a counterpoint both across and beyond the surface.

January 3, 2021.